Commemorated around the world as the day slavery ended in the United States, Juneteenth is a day to reflect on Black Americans’ vibrant culture, enduring resilience and rich history. But the words of iconic author James Baldwin remind us of a conflicting narrative: Slavery never ended for Black people in America.

Laws known as the slave codes have persisted throughout history in altered forms, from state and local Jim Crow laws enforced after the Reconstruction era to the mass incarceration and police violence that continues to plague black communities.

America’s threat of a Black genocide, to “keep a nigger in his place.”

That’s what Baldwin said to a doting crowd on Jan. 15, 1979, at UC Berkeley’s Wheeler Hall Auditorium. It would be the second and final time he would speak at Berkeley prior to his death in 1987.

The 27-minute speech, “On Language, Race, and the Black Writer,” was one of many scathing post-civil rights movement critiques Baldwin delivered throughout the country about the treatment of black people in America — poignant sentiments that, more than 40 years later, are still hauntingly relevant.

“Baldwin was saying that the civil rights movement had been revoked, because Black people after 400 years were still being oppressed, and not valued like whites,” said Cecil Brown, a Berkeley alumnus and longtime lecturer who was in the audience in Wheeler Hall that night. “He was foretelling that a revolt was coming, an insurrection against a system that oppresses black people.”

Baldwin, who lived in France, saw Berkeley in the 1970s as an intellectual hub that gave the writer a place to express disdain for American society, said Brown, a longtime friend of Baldwin’s.

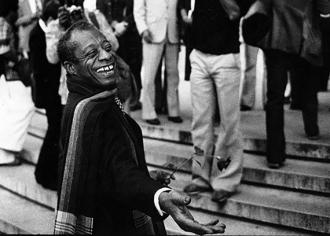

Brown remembers walking on campus with Baldwin during his 1979 visit, with the author sporting a jet-black suit, tan scarf and holding a long-stemmed rose. As Baldwin strolled through Doe Library, an affectionate crowd of students and faculty likened Baldwin to a “Black Oscar Wilde,” said Brown.

The night of Baldwin’s talk, the auditorium was abuzz with people laughing and enjoying themselves. “They were celebrating the fact that they were at the right place at the right time,” Brown said.

Baldwin’s oratory captivated the predominantly Black audience. They were so engaged, Brown said, that “you could hear a rat pissing on cotton.”

“The intentions of this melancholy country, as concerns black people, and anyone who doubts me can ask any Indian, have always been genocidal,” Baldwin, 54 at the time, told the crowd. “When you try to slaughter a people and leave them with nothing to lose, you create somebody with nothing to lose. If I ain’t got nothing to lose, what you gonna do to me?”

Baldwin’s words, heard in 2020, are strikingly prophetic.

On May 25, a white police officer in Minneapolis was captured on video using his knee to pin George Floyd, a Black man, to the ground for more than eight excruciating minutes until Floyd died. Protests against police violence and systemic racism have since sparked around the world in response to Floyd’s death and a whole host of other Black people who have died due to police brutality.

“If we had only listened, this was the slave revolt Baldwin spoke of that night,” said Brown. “Putting that knee on the neck of George Floyd, and killing him, was putting a knee on the neck of Black culture, of all Black people.”

“It’s symbolic in that way,” he added, “and Baldwin was trying to prevent this from happening.”