“It’s Never Too Late” is a new series that tells the stories of people who decide to pursue their dreams on their own terms.

One day a couple years back, the woman who has long cleaned Russ Ellis’s house in Berkeley, Calif., showed up with a new helper. Mr. Ellis did not think to ask her name.

Perhaps he forgot. Or maybe the recovering academic — a celebrated architecture professor at the University of California, Berkeley, later a vice chancellor — had other things on his mind. Whatever the case, the lapse rattled him.

“Russell Ellis, your father’s mother was born into slavery,” he said to himself. “You have the right to invisibilize no one.”

He not only learned the woman’s name then and there — Eliza — but pledged to sing it next time she came by. With that pledge, something strange shook loose in him.

“A song walked right in. Eliiiiiza. Eliiiiiiiiiza. And then the urge kept coming.”

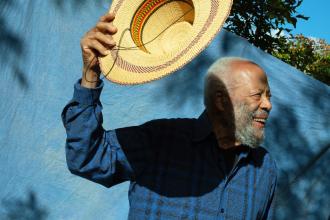

Calling on experienced musician friends to help, Mr. Ellis spent the following year recording “Songs from My Garden,” his first-ever album. He was 85. (He turned 86 in June.) It consists of 11 original songs, released online with an extremely local label, in a variety of genres.

The experience delighted him at a new level — he got to explore all new terrain, with a creative abandon he’d never known. Then, with that, he was delighted to conclude his brief recording career. (The following interview has been edited and condensed.)

Q: Tell me about your life before the “Eliza” moment.

A: I never bit down on any one thing. Over the years I’ve been an athlete, a parent, a friend, a lover. “In the golden sandbox” — that’s how I think of my life in California. As a kid growing up in the working-class Black world, you wanted a secure job at the post office or teaching school. But doing new things has always been part of my life.

After retiring, I got into stone carving, then modeling clay, then steel work and painting. Sometimes I’d see former colleagues from Berkeley and they were still kind of wearing the clothes of the old office. I couldn’t have been happier to let go of all that.

How hard was it to start writing music for the first time?

Not hard at all. The songs just started coming, easily and naturally. I have always been a laborer, but I suddenly had the experience of a muse saying, “I gotcha, I’m taking over.”

What did it feel like, doing this entirely new thing?

Having that muse — it’s like I was accompanied by another self, more sophisticated and supple than I was. I’m an empiricist. But if I had to romanticize, I’d say it was a spirit that came to visit. It was one of the best experiences of my life. What a joy to have stuff flow like that.

One side effect: You know how you get a song in your head sometimes? I now get whole orchestrated movements. New doors still open as you age. Along with creaky limbs, interesting things happen, too.

How did you learn about recording and songwriting?

I’m kind of connected to the musical world through my children and their friends. I exploited any contacts I had: Would you mind helping me with this for free? Everyone was very generous.

Were you nervous, taking the first steps into this new world?

There are benefits to age. Not a lot, but some. I’m too old to get nervous. And nothing was riding on this.

What kinds of challenges did you encounter at the beginning?

The hardest thing was the blues. Recording my song “Night Driver (The Next-to-Last Old-Ass Black Man’s Bragging Blues)” was intimidating. Singing the blues ain’t just something you stand up and do. You have to be in it, you have to mean it, you have to deliver it in a way that people get into it themselves.

How did this album change you?

A big surprise to me about aging is that you do keep changing. I think doing the album made me a kinder person. Having my kids’ clear respect and support with it — it helped me feel better about myself, and when you feel better about yourself, you feel better about other people.

Also, I was onstage for a living, teaching classes for 150 students, then representing the university in my administrative role. Before that I was a track star at U.C.L.A., from ’54 to ’58. If I ran a good race, my stroll across campus was an act of celebrity.

All that stage time was not good for me. I felt somewhat unreal. I realized, when I finished this album, that was my last expression of my desire for it. I have been happy to get offstage.

What’s next for you?

My wife is suffering some significant health problems. It’s normal trouble, as they say — but it’s not trivial. Right now my life is about caregiving.

What would you tell someone who’s feeling stuck in their life?

Do something that involves other people. Even one other person. Getting out of a groove — sometimes you just need company.

There’s this fantasy that creativity is something you do alone, by candlelight. No! Do something with other people who are as genuinely interested as you are.

What do you wish you’d known about life when you were younger?

That doesn’t involve sex?

Life is shorter than you think and longer than you think. My two best friends are also Black men in their 80s. We marvel about our actuarial improbability. I’m happy to have used my time in so many different ways — ways that connected me to the world, to people.

Were there experiences before the album that helped prepare you for it?

Over the last 10 years I’ve actually had a bit of an art career. In the process I discovered that I wasn’t as vulnerable as I thought. At one point I had a piece in a group show, at a gallery. I walked by it just as a guy was saying, “this painting sucks.” And I didn’t die! I actually went over and, without telling him I was the artist, asked why he said that. Turned out he was a painter, and he told me his reasons. I learned a whole bunch.

Any other lessons you can pass on?

Take note of what’s interesting in your life. Don’t keep every little scrap of paper. But take note.