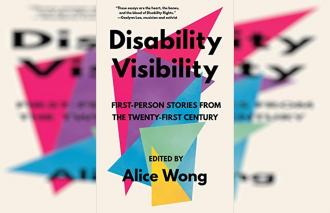

The official launch of Alice Wong’s Book, “Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories From the Twenty-First Century” took place during an online event July 25. Wong is a well-known disability activist based in the Bay Area and a presidential appointee to the National Council on Disability under the Obama administration. Wong founded the Disability Visibility Project, which records and amplifies disability culture.

The anthology contains deeply personal stories by the authors focusing on their lived experiences spanning a range of disabilities. As Wong went on to explain during the online launch, the stories were carefully and lovingly selected and ordered to provide a deep dive, acting as “an invitation for people to learn and grow and to want to learn more.”

Indeed, even though each story may have more meaning for different populations of disability, there is something to learn from each story for all readers, disabled and nondisabled.

The book launch included a panel of some of its contributors — Patty Berne, Haben Girma, Ariel Henley, Lateef McLeod and s. e. smith — and was moderated by local disability activist Yomi Wrong.

In her introduction, Henley talked about her passion for facial equality as she has a facial condition in which the bones in the head fused prematurely, giving her an asymmetrical face. Henley said growing up, there was no information about craniofacial conditions even as she faced multiple traumatic surgeries, and she now has found purpose as a resource for the younger generation.

UC Berkeley alumnus McLeod discussed his chapter, which is about gaining power through communication access. McLeod is a doctoral student in anthropology, has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair as well as alternative and augmentative communication, or AAC, technology, which helps a minimally speaking or nonspeaking person to communicate. He spoke of how augmented communication allows for expression and engagement with members of the community as well as how advancement in this technology could widen possibilities. McLeod also said he would like to see more stories of AAC users so that people will have the opportunity to empathize with their experiences.

Girma, author of the memoir “The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law,” highlighted the interdependent relationship she has with her guide dog. Girma clarified how “the guide dog depends on the person’s confidence, knowledge, direction and orientation skills.” What this means is that the blind person is in charge and not, as is assumed by a layman, being led around by the guide dog.

Girma also said she would like to see stories that center on the person and what they are doing, rather than on the technology or the service animal that helps them. “Instead of asking me, how do you overcome your disability? Ask me, how did Harvard overcome its ableism? How did society overcome ableism? And there’s still more work to do both for society and for Harvard,” Girma said.

In response to an audience question on “Crip” identity, Wong went on to explain that some in the disability community now choose to identify as “Crip,” almost as a way to reclaim the word “cripple” and use it aesthetically, thus subverting its harmful historical use.

smith said his essay focuses on a Crip space that is for and by disabled people, which can nurture disability joy. Crip spaces can make nondisabled people feel uncomfortable, and this is something smith said he wanted to focus on in his essay — that nondisabled people need to learn to accept that. smith also pointed out how the recent police violence against protesters and the long-term health implications from the COVID-19 pandemic could end up with more people entering Crip space.

Berne, founder of the Bay Area-based Sins Invalid, drew parallels of surviving climate change in her story to the way the pandemic has not left any part of our globe untouched. She stressed that it showed that “any movement we organize has to be a healing movement. It has to heal and simultaneously advocate for justice.”

Berne also expressed a desire to see conversations about the meaning of social capital within disability, which means the uplifting of marginalized groups within the disability community itself. “There’s no freedom if any one of us is left behind,” Berne said.

Wong’s anthology also has a plain language translation by autistic journalist Sara Luterman, the first such translation in the adult nonfiction arena. As Luterman explains in the forward, this means simpler sentences, the use of only the 3,000 most common words in the English language and getting the text down to a fifth grade reading level. The intended audience is still adult readers and the translation does not presume the audience to be just white.

Luterman calls the plain translation a “radical new kind of accessibility” in order to help people understand ideas that matter. “There are many reasons someone might not know the right words … disability … second language … access to education. Sometimes, it’s all three,” Luterman explains.

Contact Hari Srinivasan at hari@dailycal.org.